Drafting #

This article is still a work-in-progress. Check back soon for a completed version.

2018 Talledega. Photo courtesy of Stewart Haas Racing

Introductory Thoughts #

Drafting, or slipstreaming, is a common sight in any motorsport race. The underlying physics are more elaborate and unintuitive than they given credit for, so it is worth diving into the technical aspects.

Before Proceeding…

Readers will be best served by reviewing articles ‘Basics I - IV’.

The Physics #

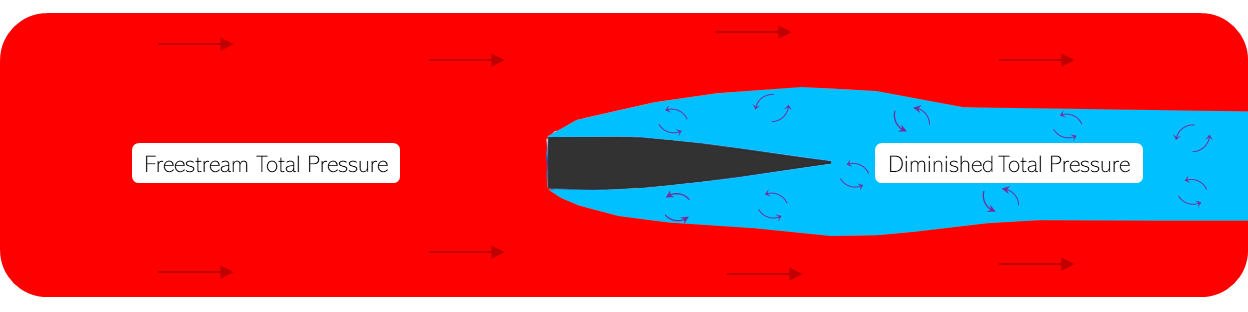

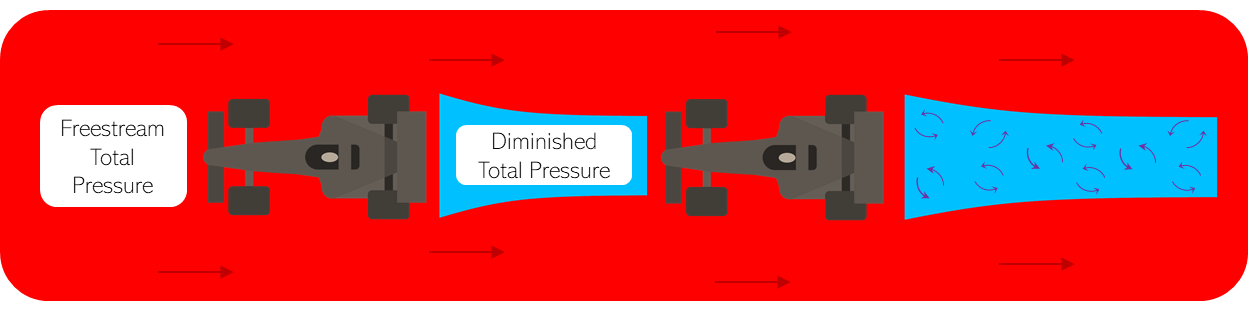

As discussed in the Basics III article, a bluff body has significant total pressure loss and drag. Most racecars are heavily on the bluff end of the form spectrum as a racecar extracts as much total pressure from the flow as it can to generate downforce.

However, racecars don’t race in isolation. When all of the cars are out on track at once, they all fight to use the limited amount of energy in the air for their own aerodynamic needs. Often times, by virtue of being out front, the lead cars get an uneven share of that energy.

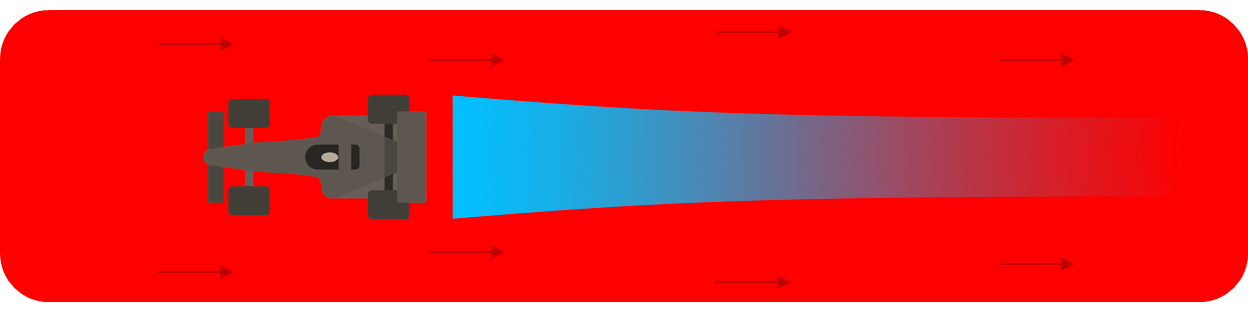

The flow does work on the lead cars, leaving behind a wake of air that not only has less total pressure (less energy), but is also turbulent and unsteady. By virtue of this, this flow can do less work on the cars downstream.

Sufficiently far enough downstream, the turbulent flow mixes with the surrounding air to a degree that makes the wake eventually imperceivable. Correspondingly, whatever positive or adverse effects are associated with following within the wake also die out with distance.

This can be easily visualized when cars race in the rain. The turbulent wake mixes within the water to create a fine mist.

2011 Canadian Grand Prix. Photo courtesy of Formula One.

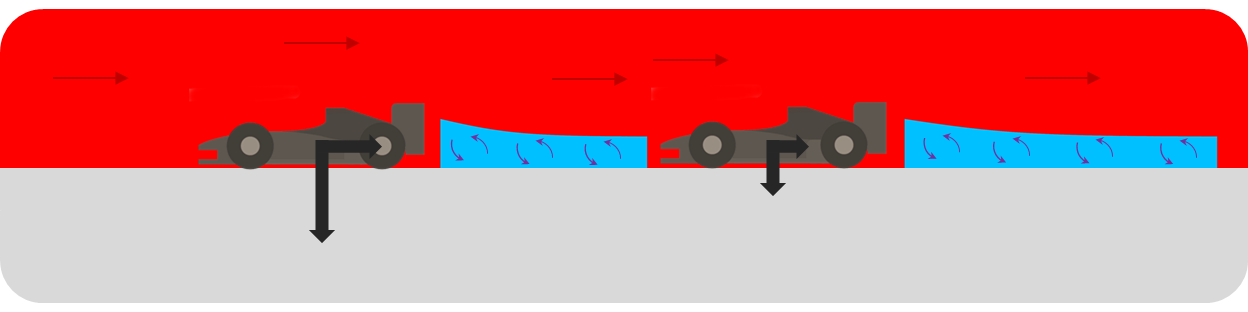

Effects On Racing #

In the corners, a loss in downforce directly leads to a loss in grip and therefore cornering ability, and therefore a trail car will be unable to match the cornering speeds of the lead car. However, on the straights the trail car has less drag than the lead car. Often times this leads to a yo-yo effect over multiple laps, where the trail car falls behind in the corners, catches up in the straights, and falls back in the corners again. Eventually, if the straight is long enough, the car behind will be able to use that slipstream to overtake.

Often times the trail car will pull out laterally from the lead car through the corners. This is geometrically a slower racing line, but it allows the racecar to maintain some of its downforce through the corner.